| J. Phillip Thompson |

This essay compares a version of Economic Democracy (ED), in a thumbnail fashion, to two trends that have dominated thinking about the economy over the last two centuries; I label them ‘productivism’ and ‘price theory.’ Many books have been written on these topics, and a brief essay cannot begin to do justice to the many insights, arguments, overlaps, and nuances on all sides. Nonetheless, there are big enough differences between these different trends to at least establish them as distinct trends, with important consequences. The essay assesses how these concepts differ in four areas: (a) how they interpret value? ‘Value’ in economics refers to who and what contributes to overall economic well-being and prosperity; (b) their analysis of how community relates to the economy; (c) how they explain alienation, or social hostilities related to the economy?; and, (d) their understanding of the role science and technology plays in the economy. At the end, I address potential criticisms of ED from the Right and Left. For those not wanting to read the entire article, please read Section V at the end on criticisms from the Left as it is more or less a summary of the paper.

I. Productivism

Who and What Creates Value?

Early (19th century) political economists such as David Ricardo and Karl Marx (who adopted Ricardo’s labor theory of value) argued that value was created by labor (workers) during the course of production. I label this trend ‘productivist.’ For productivists, the value of an item depends on how much labor it took to produce it. The price of labor was a combination of the cost of reproducing workers and the result of struggles between workers and employers over wages. This was a widely held view in the 19th century. Since people regularly saw workers plowing fields or stitching together products right in front of them, it seemed almost self-evident who and what was creating value. Today, with production of goods usually out of sight (and country), and with machines and software doing “work,” the connection between workers and value creation is less apparent.

Community

The founders of the US constitution had a weak sense of community, or the “We” of “We the People.” They restricted voting to property-holding white men. Racism and sexism aside, part of their reasoning was that political participation required time and education that only people with economic means could fulfill. Worries about mass political participation by street mobs steered by demagogues were heightened following the French revolution, where not only monarchists but left-wing democrats and anti-slavery advocates were suppressed, and sometimes executed. Yet, the corrective for such destructive mob action, e.g., providing ordinary citizens with the time and resources to effectively and wisely participate in governance, was not resolved during the founding or after. More than a few of the Founders believed that ensuring widespread property ownership was a way of making non-elite white men more responsible and capable citizens. Thus, when voting rights were extended to white men in the early 1800s, it was accompanied by aggressive seizures of land occupied by Native Americans in order to distribute the property to white males. Democracy, including civic participation of white men, emerged on the backs of native peoples, black slaves, and women. Civic participation of the excluded majority of the population, which the community issue raises, was pushed aside.

Marx, a productivist in economics early in his life, theorized from England about the impact that emerging capitalism would have on civic organizations and popular consciousness. He argued that capitalist industrial organization was leading workers to associate in factories and cities, and their common fight against exploitation on the job would lead them to embrace ‘class consciousness,’e.g., that class rather than ethnicity or religion or nation would become workers’ main form of identity. Marx was partially correct. Trade unions did grow out of workplaces and became an important component of civic participation for workers, especially for white male workers in cities in the US and Europe. Marx did not deeply consider how slavery, colonialism, or women’s role in society would affect workers’ sense of community.

Alienation

The German philosopher Hegel argued that human beings are linked together and dependent on one another, even when this mutual dependence is not socially recognized. Marx took this insight from Hegel and argued that capitalism (private ownership and control of large businesses) alienates workers from the products of their labor, and makes it seem as though the products of mutual efforts between workers and business owners belong only to the owners and investors. Because the role of workers is not recognized when owners put products up for sale, Marx argued that the entire system of capitalist alienation was embodied in the existence of each and every ‘commodity’ (a good for sale). To illustrate what he meant, imagine that a bunch of workers who make home building products in New Orleans became homeless after Hurricane Katrina. They also lost their jobs and income. When they went to HomeDepot, they saw a huge supply of homebuilding products they themselves had made, much of which would never sell because so few people had money after the hurricane. Yet they could not use the products they made to rebuild their homes, because they too didn’t have money. This is what Marx meant by people being alienated from ‘commodities’ that are actually the products of their own labor. Such alienation often makes little sense from a practical and humanistic standpoint. Making sense of deprivation in the midst of plenty, as in the New Orleans example, requires taking in an entire range of ideological arguments about the inherent benefits of capitalist social relations–that Marx argued were little more than smoke intended to confuse and mystify workers. The Hungarian economic historian Polanyi, writing in the mid-20th century, similarly noted that capitalism created entirely novel situations in human history where starvation took place even when food was available in other parts of the same community.

Another part of alienation might be seen as inevitable. Hegel argued that people come to know things through interacting with them over time, e.g., knowledge is developmental and retrospective. Marx built on this perspective to develop a theory that all people first encounter capitalism lacking an understanding of its nature and consequences. Over time, workers gradually realize that capitalism has made them into an exploited “class,” and that they would be better-off running the economy themselves. This transition process Marx described as a class, “in itself,” becoming a class, “for itself.” Alienation of people from capitalism would be overcome by the actions of the people based on their gradually developed understanding of the system, and then their action to change it. There are many who now argue, however, that the entire classical tradition of social theorizing in terms of entire systems such as “capitalism,” “market society,” “socialism,” or “democracy,” creates an illusion of coherence and irreversibility of social institutions which robs people of their agency. Law, government structure, and markets, are the cumulative result of innumerable political struggles and compromises at various points in time. Once established, these institutions affect the present, but they do not determine the course of the future—people do. In this view, grandiose theorizing is itself alienating, and so is positivist social science which takes current institutional arrangements as an unquestioned given.

Technology

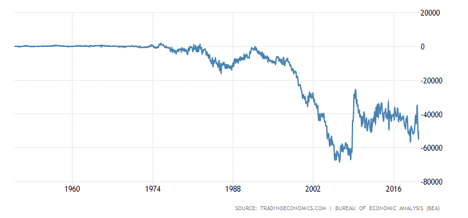

Marx was one of the original theorists of technology. Again leaning on Hegel, Marx viewed capitalism as a stage in human development that would be superseded by other stages. In unfinished later work, Marx argued that his productivist approach was only valid for the earlier stage of capitalism. In late capitalism, human labor would be displaced by science and technology. Science and technology would be the product of “social knowledge,” developed through schools and intellectual discourse, and not reducible to individual worker or entrepreneurial inputs. As science and technology enabled enough production to take care of basic human needs at little cost, there would be little reason, other than capitalism’s antiquated social relations, to limit workers’ interests in pursuing their passions for art, sports, literature, exploration of new frontiers, etc.. Marx also theorized that as technology replaced human labor, under-employed workers would not have enough buying power to sustain profits, thereby leading to stagnation in advanced capitalist countries. Many economists argue that this is consistent with what the US has been experiencing over the last 20 years. We will return to this theme at the end of the essay.

II. Price Theory

Who and What Creates Value?

Government policy, and general thinking about the economy, has been primarily guided in recent decades by a narrative variously called “neo-liberal,” “marginalist,” and, “choice theory.” I will group these under the label “price theory” of value. Price theory is an image or story about how the economy works. Like productivism, it is not an empirically settled research finding. Problems in the productivist narrative created space for rival 19th century interpretations of how value is created. In price theory, value is determined by how much money (the marginal amount) people are willing to pay for an item given their other priorities. The price narrative seems commonsensical today because it fits with our current consumer experiences, where most people think of the economics in terms of shopping rather than themselves making or growing the things they buy (only 11% of the US workforce make or grow things). Unlike productivism, price theory leaves room for psychological factors like fashion, having nothing to do with the amount of human labor expended to make a product, that may drive the value of a good up or down.

While price theory has a more sophisticated view of the consumer side of the market than productivism, its approach to social relationships during the production process is wanting. Price theory takes a flat face-value approach to evaluating the contributions people make to the economy. Opposed to the productivist view that producers (workers and farmers) put value into their products which is then represented in prices, price theory turns things the other way around. If people are willing to pay a given amount for a product or employee, then that is what the product or employee is worth. They posit this not only as a statement of fact in terms of money payments, but as a peoples’ verdict of actual value to the economy. People and firms making the most money is considered as evidence that they contribute most to the economy. Adherents call this “the market speaking,” and argue that is it similar to democracy. Yet in this “market speech” only money has a voice. Price theory became popular in direct opposition to workers’ and socialist movements in the late 19th century, and again in the late 20th century in opposition to domestic and global movements for economic equity.

Community

Price theory’s contention that the value of something consists of what people will pay for it, and that market speech is freedom, is a kind of (libertarian) anarchism. In this worldview, entirely unsupported by empirical evidence, people are considered as self-interested atomized individuals. Their market “speech” is not a spoken language between people, it consists of data on how individuals spend money. ‘Community’ to them is simply an agglomeration of actors sharing like self-interests; what really matters are individual choices. To understand why this is anarchistic, we need only to take a step back. Is what is good for society simply the sum total of individual desires? Are what individuals desire necessarily what’s best for them? Wouldn’t the answer depend on how their desires came about, or their level of maturity? For example, is a young persons’ desire to smoke cigarettes the result of her education about the risks of smoking, of robust and informed discussion about smoking with family and teachers, or is it the result of heavy marketing to children of candy flavored electronic vapes, and of peer pressure during junior high school? If the latter, would we still say that vape and cigarette sales contribute value to the economy? Would we say that we don’t need civic associations or government to play a role in guiding young peoples’ thinking, or in regulating cigarettes and vape? Similarly, does a family willing to pay more money for a house in an all-white neighborhood mean that all-white neighborhoods contribute more value to the economy? Are we okay with people choosing housing based on race, with no consideration of its effects on the larger community and democracy? Price theory would be silent on both questions, because price theory has no concept of social value, or of human development, or of how civic institutions are needed to shape values in ways that create mutual prosperity and wellness. This libertarian anarchism slides into corporate domination when corporations have free rein to influence peoples’ preferences for the narrow aim of selling their products. We saw this during Facebook’s and Twitter’s acquiescence to white nationalist and fascistic use of their platforms to undermine the legitimacy of the 2020 presidential election. Unrestrained “free market” anarchistic capitalism leaves little role for civic associations, social ideals, and government; it provides corporations with an open field to control or undermine democracy.

Alienation

Although some neo-Marxist versions of price theory (choice theory) discuss the clash of self-interests between workers and business owners, price theory gives little attention to alienation. Labor domination and exploitation are important topics for productivists, but price theory focuses narrowly on individual market choices. When it comes to income distribution, price theory simply assumes workers are paid according to their economic contribution (their ‘marginal product’); there is no exploitation. Opposition to this “neo-liberal” blind-spot undergirded labor’s opposition to the Obama administration’s global trade initiative (TPP). Allowing “the free market” to set prices for labor ignored the fact that some European countries subsidize certain industries for political reasons, and that other countries allow child labor, e.g., there is no such thing as a politically unmediated free market. Price theory can lead to absurd ideas, including how the US measures the Gross National Product (GDP). Many things that cost a lot of money, and are therefore counted as adding value to our GDP, in fact do the opposite. High healthcare spending, for example, is counted in the GDP as adding value, but it mostly reflects poor community health and administrative waste.

Price theory operates at such a high level of abstraction that it tends to blind people to real world exploitation and the human cost of economic choices. Landlords, for instance, who own apartments near transit stops, or near workplaces in cities where housing is scarce, can jack up prices, thus diminishing resources young renters need to continue their education or maintain their health. Raising the rent does not make landlords value creators, as the price narrative suggests. Similarly, price theorists have glibly assumed that workers can move to whatever part of the country offers incrementally higher wages for their services—this is how, they say, the market achieves optimum efficiency. A workers’ family history (their parents and grandparents buried in the local cemetery) and community ties with church and neighbors do not matter in their calculations—neither does mental health.

Price theory also grossly mischaracterizes the role of government and civic actors in creating value. In their view, government is an interest group just like corporations. Government policies, however, not only impact markets, they determine what markets will be. For example, banks depend on federal insurance to attract deposits that they can then invest. Otherwise, financial markets would shrink. Very often the private sector takes credit for value created by government and civic actors. Uber makes profits, for example, but the institutions that make Uber successful include the federal government which made risky long-term investments to develop GPS and the Internet, the universities that did the research for government, the state and local agencies that build roads and maintain street lights, and the public schools that taught consumers and drivers how to read. Government, universities, public schools, community non-profits, and workers all created value that Uber takes advantage of. Misunderstanding value creation lies behind the conservative notion that government should stay clear of business, and that non-profits and public workers deserve less compensation than private sector ‘value-creators.’ Not only factory workers are alienated from the fruits of their labor in neo-liberal practice, so are government actors and non-profits.

Technology

Price theory imagines little beyond market transactions and lacks conceptual resources to think through the social implications of current technological developments. With their focus on individual choices, price theorists often imagine that they are getting down to the granular essence of human behavior in a way that parallels natural science. They develop extensive mathematical models in an attempt to prove that the economy strives for states of optimum “equilibrium” in much the same way that the human body strives for equilibrium. Imagining the economy as a natural (or supremely rational) organism, they do not imagine another economic system superseding this one. When confronted with the challenge of technology displacing workers, and thus continually depressing consumer demand, they turn to ad hoc fixes like Universal Basic Income (UBI), e.g., giving workers money to keep demand going and prevent economic collapse. Yet, technology poses other challenges beyond reduced consumer spending. The most dynamic parts of the economy today are driven by science and technology—software, computers, robotics, bio-engineering—and science and technology emanate from the brainpower of highly trained scientists, engineers, machine operators, etc.. Such brainpower comes from the widespread cultivation of peoples’ abilities, and not only or especially market actors. The creators of scientific and technological capacity are typically people who don’t sell anything at all: government employees issuing research grants, teachers at universities, and school teachers who educate and cultivate children. In the price narrative, where one’s income determines worth, these key contributors to the tech economy are made to appear relatively unproductive and unimportant, and brainpower is massively underdeveloped.

III. Economic Democracy

Who and What Creates Value?

Beyond biological and ecological necessities, human beings decide what they value in the context of their upbringing and social environment. The key question is how; through what structures and developmental processes do people make value decisions? Broadly speaking, there are three ways people can express their economic priorities. One way is through the market. We can question whether people’s priorities, especially poor peoples’ needs, are meaningfully captured through an impersonal system where individual consumers make choices solely through what they purchase—as the price theory model maintains. Another way is through government. There are a few countries where government planners decide what and how much to produce or buy for the entire country. This is the state socialist model, which has proven problematic in incentivizing innovation as well as in meeting citizen demands for a diversity of products. A third, and least familiar approach in the US, is a ‘civic-economic’ or cooperative model where citizens (workers and consumers) directly govern businesses across the spectrum. The concept of ED is often conflated with cooperative firms, however it can apply just as much to market-dominated and government-dominated economies. The key is that citizens are enabled through civic intermediary organizations to steadily develop and expand the scope of their collective and informed decision-making about their value priorities. In a market society like the US, citizens can organize collective purchasing groups to reward firms that comport with their priorities, and shape markets that way. They can also organize for participatory pension management through unions, they can organize masses of shareholders in big companies. And, they can use their voting power to pressure government to impose rules and regulations over market actors. All this is in addition to increasing the number of cooperative firms. In practice, most countries mix all three of the above systems in different ways. For example, Scandinavia has more government planning (social democracy) than does the US. Parts of Spain, Italy, and Canada have a lot more cooperative firms than the US.

Why is putting citizens at the center of economic decision-making important? First, it guards against tyranny and exploitation. Many call the US economic-political structure an oligarchy (a form of tyranny) because of the excessive influence of a small number of wealthy donors (from large corporations) on government. Second, ED enables workers and community members themselves to define the common good, not private firms claiming to speak for the people, in the forefront of public policy. Private profit-seeking firms do not develop products or innovations to benefit the general public, unless it makes money for them specifically. Many things citizens need and want, clean air for example, do not emerge from private firms. Last, ED focuses on building bonds among citizens and humanity beyond our borders. In ED settings, citizens are able to deliberate collectively through an array of ‘civic-economic’ intermediate organizations that are not government-controlled or manipulated by big corporations. Citizens debate and agree upon their economic priorities, which are then expressed in their individual capacities as voters and consumers, but also through the policies of an array of worker-owned ‘civic-enterprises.’ The goals of ED mirror those of political democracy. A key argument for ED is that it provides a practical means and multiple venues for developing habits of good citizenship, good governance, and shared prosperity, on a daily basis. The absence of ED is threatening political democracy.

Government is critical for ED. For starters, government is needed to curb and compensate for inherent disfunctions of markets. As the economist Keynes argued nearly a century ago, the public cannot trust markets to function smoothly based on individual choices, as price theory argues, and must intervene when people act out of irrational “animal instincts” like fear, hysteria, or ‘group think’—such as when the economy froze in 2007. Also, left alone, capitalism’s drive for ever higher profits, and ever lower wages and taxes, makes life unbearable for most of the population. Workers’ use of democracy to win government relief measures are ironically what enables capitalism to not self-destruct. Government regulation of the market economy, and smoothing out of its unequal outcomes, helps ED to develop by stabilizing markets. Government is also needed to bolster and protect civil society from domination by powerful private actors such as corporations. Labor unions, for example, have a hard time staying in existence without laws ensuring freedom to organize and fair bargaining.

Government powerfully shapes the economy in a myriad of ways. Allowing the Federal Reserve to operate as a private agency, for example, provides money to banks with no requirements beyond return on investments (profits). This structure empowers private banks to be major decision-makers in the economy. Through taxation policies, government regulates how much inequality is permissible. Government also sets the rules that shape markets, and helps determine winners and losers in many markets through its procurements and subsidies. What’s even less understood is that government is the nation’s leader for innovation. Many key innovations, such as computers and the Internet, took many years of patient investment with high risks—no venture firm would do that.

Government is also the most powerful means for transforming the economy towards ED. Government could dramatically increase public and civic ownership and voice in the economy in a myriad of ways. Government could easily take ownership shares when it invests in companies, or put policy requirements on such companies. Tesla, for example, received a $465 million loan from the Federal government in 2009. Unlike a venture capital firm, the Federal government only asked for shares of the company (3 million shares) if the loan wasn’t paid back. Since then, the value of Tesla stock has soared, making Elan Musk one of the richest persons on earth—government got none of the upside, nor any voice in the company. This is the typical approach for state and local government as well. Our economic ills can be powerfully addressed by redefining government’s role in the economy, in addition to democratizing how firms and other economic institutions are owned and operated. Government’s role in the economy should be to: (a) provide for the social and physical infrastructure needed for both people and enterprises to thrive; (b) educate the public on the value of social cooperation (multi-racial democracy), and enable citizen participation and control over major economic decisions; (c) ensure that markets are inclusive, diverse, and equitable; (d) protect the earth. ED moves toward a society where citizens are better educated and knowledgeable about economics, well paid, and engaged in economic decision making at all levels: on the job, in community-owned ventures, through stock and pension management, and through officials they elect to serve in government. Such a society needs a robust and independent civic sector including independent media and universities, non-profit advocates and watchdog groups focused on both government and economic institutions. ED would encourage, or at least remove many economic obstacles to, cross-national cooperation fostering equitable development world-wide, as opposed to militaristic approaches in support of economic predation.

Community

Community, from the local level stretching to the transnational, is the central concept in ED. This section begins by explaining why Americans tend to have a narrow individualistic idea of freedom, one that is separated from community membership. I then argue that freedom in the US has long been racialized. Ways to overcome racial division and establish a common attachment to community are then discussed. The section ends with a discussion of the need for civic infrastructure to realize the promise of democracy; ED is a key part of that civic infrastructure.

Freedom

To build a vision for community life in an ED, it is useful to tie in the concept of ‘negative’ versus ‘positive’ freedom. Negative freedom means the absence of domination, usually from the state. If government does not interfere with the content of mass media, for example, then the press enjoys negative freedom. Positive freedom concerns (at least) two things: the actual ability (ways and means) of citizens to pursue their goals in life; and the actual ability of citizens to make government, and we would say also big corporations, adhere to their collective will. Positive freedom advocates maintain that the ability of citizens to make government bend to its “collective will” goes beyond having elections and counting individual votes; to truly hold government officials accountable, citizens need time, money, an independent media, ways to monitor elected officials, and ways to deliberate constructively with other citizens. Positive freedom is implied in the notion that government authority is based on the “consent” of the people. In order to give consent in a meaningful way, citizens must be aware of what they are consenting to, which suggests they already have the capacity to collectively “self-rule.” What is meant by “self-rule” is that citizens have the ability to formulate proposals, to freely debate and deliberate ideas with other citizens, and then to have their priorities implemented. In the US, freedom is generally understood as “negative,” which does not require a rigorous evaluation of civic capacities, nor thinking much about others.

Freedom and Race

There are good reasons why a thin negative concept of freedom predominates in the US. It’s largely because freedom was defined, for hundreds of years, against the backdrop of slavery. Not being forced to labor for free; not being physically confined to one’s place of work; not having your employer totally control your family and personal life; not having any rights against the state; these were all negative liberties that white men had, and slaves did not. Comparing their condition to slaves, white laborers felt free simply not to experience social death. White workers’ freedom, limited as it was, was inseparable from their being considered “white.”

Positive freedom would have meant the ability of early Americans to formulate, through associations of their own, policies they wanted government and major economic actors to implement. Some of the more radical Founders (and grassroots dissidents) had such a vision for the US, but to demand popular power of this magnitude was too much for most Founders (a majority of whom were slaveholders) who were concerned that the popular masses would seize property. (This is how the US ended up with such a mal-apportioned Senate.) Today, the technical/bureaucratic apparatus of government and the lop-sided political influence of large corporations are obstacles to positive freedom, and like before, elite resistance to popular participation and power remains strong. Elites, however, are no longer the main impediment to ordinary citizens obtaining the ability to govern the economy. The greater barrier is racial division amongst the people: division elites cultivated after the founding for even greater protection for property than the barriers erected through the structuring of the US Senate, Electoral College, and Supreme Court.

Racial division disables constituting the “we” part of, “we the people.” There has never been a broadly accepted sense of community, collectivity, or “we,” in the US. Historically, no ideological trend has been as convinced of the inevitability of solidarity among workers across race as followers of Marx. Marx called white workers’ desire to be considered as “white,” “false consciousness,” in the belief that their material interest in solidarity with non-white workers–especially when thrown together in factories and city slums–would cause them to eventually abandon white identity. Yet, this did not happen; it is a prime example of 19th century theoretical overreach. W.E.B. DuBois, revising Marx, coined the term “psychological wage” to make the point that white identity meant more than money to most “white” workers. Marx did not anticipate that racial segregation in housing, schools, and other parts of civil society might create formidable physical barriers between workers, and instead of cross-racial solidarity growing out of workers’ lived experiences, the opposite might occur.

Taking insights such as DuBois’s into account, black advocates and scholars have for two centuries attacked the dominant American narrative of a consensual “we the people.” To have the population considered as a “we,” there should be some sense among the population that they belong together, a willingness of different parts of the population to listen to one another, and enough mutual respect to uphold the rights of others–such as the right to vote. Even today, neighborhoods, public schools, churches, and social organizations are de facto racially segregated between whites and blacks, and to a lesser degree between whites and Latinos. This civic separation structures political division.

Racial domination also takes place through the resource inequities across civil society. Aside from labor unions, civic organizations are funded through member contributions, corporate donations, or foundations funded by wealthy individuals. Low income communities, and especially black and Latino communities, have limited resources than can be tapped to establish participatory civic organizations. Corporate donations steer civic organizations towards compliance with their corporate priorities. Foundations are more varied, but typically offer small grants, and they also steer civic organizations towards the changing priorities of the foundation boards. Although many students of civil society call for increased funding for civic organizations to improve democracy, none to my knowledge have proposed alternatives to the three options above, thus continued dependency of black and Latino groups on white (tax subsidized) charity.

I traced above only the surfaces of racial division in civil society, its moral underpinning is white racial hatred and unwillingness to associate with people deemed inferior. Overcoming this division is the key to extending a full (positive) democracy. Overcoming requires two kinds of work: constructing multi-racial democracy as a counter-narrative and counter-culture to racial superiority; and, engaging people from all races and backgrounds in common work and dialogue. Before discussing some next steps on these issues, I want to discuss DuBois’s view on how power is constructed in the US.

DuBois argued that Western capitalism’s origin in slavery led civil society and government to be structured as a racial hierarchy. The inculcation of racial hierarchy was initially to justify and support a settler slave-capitalist system. Later on, racial hierarchy became important for maintaining popular white support for sustaining capitalism, especially during economic crises. Opposition to capitalism, and calls for economic reform, were frequently derided as synonyms for racial integration—which no decent white person would want. Even so, the content of white privilege offered few positive freedoms for whites: sometimes white workers got slight wage differentials above workers of color; if black workers were available, white workers might be spared the very worst jobs in a factory, farm, or household. White workers recruited into the police and military were celebrated, especially for their essential assistance in supervising and repressing non-whites. Still, the system was fragile. When an inter-racial movement of farmers and workers (Populism) emerged in the late 1800s, the government went so far as to forcibly segregate (through the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision) the nation by race. For black people, this meant that civil society and the market were not even areas of negative freedom.

Once government and cultural institutions took a certain shape, they were not bound by the conditions of their origins; they developed a life, logic, and dynamics of their own. This has enabled racial division to play multiple roles throughout US history. For example, the shift from slavery and Jim Crow economies hasn’t made race less important. In the last half century, while black people’s role in the economy has diminished, their importance in politics has increased and the political value of anti-black racism has far exceeded the direct economic value of super-exploiting black people on the job. Racial division and the narrative of undeserving blacks winning unfair advantages via government policy and programs in fact has facilitated conservative and corporate power over the entire governmental apparatus, from foreign policy and taxes to the environment, enabling wealthy corporations their best means for gutting government while enhancing their own fortunes with tax breaks and other advantages.

Our emphasis on multi-racial ED stems from the above, and differs from ED advocate efforts that narrowly focus on providing workers with more voice within firms, or on forming coops. Like traditional trade unionism, these latter ED efforts follow the productivist legacy that workers’ material incentives for solidarity will outweigh racist culture and politics. The reasoning goes back to 19th century assumptions that the traditional Left shares with the Right. This is the view that human beings are primarily individualistic and materialistic, and that other aspects of their identity like their race (or gender designation) supposedly pale in comparison. Yet, we cannot expect ED to broadly expand and stay on track without abandoning this naïve belief in automatic economic solidarity and addressing the country’s racial divisions: squarely confronting conservative manipulation of deeply rooted racial animosity to battle multi-racial organizing— a strategy they know to be the best approach for propping up corporate oligarchy. This will not be an easy task, it requires lots of resources and new methods for countering racial domination in civil society.

How do we engage people who see no reason to do so? I mentioned the need for material incentives, but economic interest has not been sufficient historically. We need to change the culture that gives rise to racialized (superior/inferior) identities. There are many strategies for such engagement (and a need for more), none of which are contradictory. We could follow Frederick Douglass’s approach of lifting up the revolutionary aspirations of many of the Founders of the US, and thereby redefining the meaning of being a US citizen. In Douglass’s 1852 July 4th speech, he focused on the more radical of the founder’s: “They were peace men; but they preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage. They were quiet men; but they did not shrink from agitating against oppression. They showed forbearance; but that they knew its limits. They believed in order; but not in the order of tyranny. With them, nothing was “settled” that was not right. With them, justice, liberty and humanity were ‘final;’ not slavery and oppression. You may well cherish the memory of such men. They were great in their day and generation.” Continuing in this vein, countless white Americans have indeed fought racism, and many gave their lives for this cause, yet few Americans know this history because it has been buried. For example, large numbers of European revolutionaries joined with the US abolitionist movement and volunteered to fight during the US Civil War. Many of the officers of black regiments during the war were drawn from the ranks of abolitionists and European revolutionaries. By the end of the war, over half of the Union army consisted of black and immigrant soldiers. Courageous farmers and workers joined inter-racial movements such as the Populists and IWW during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Many white activists fought side-by-side during the civil rights movement, and many died doing so. There is no shortage of white anti-racist heroes, showing that there is not only one way to be white, but there is not even a name for this powerful white anti-racist trend in the US. Similarly, there are many examples of black Americans fighting against the oppression of Asians and Latinos, and vice-versa. Again, there is no name for this trend. Giving names to these longstanding struggles for an inclusive multi-racial democracy, and re-educating Americans in schools and media on the fight that has made America democratic (to the extent that it is), is fundamental to moving beyond negative critiques, and creating an appealing national identity Americans can take pride and inspiration from.

Douglass’s rhetorical strategy may have influenced Howard Washington Thurman, whom I’m told profoundly influenced Martin L. King’s rhetorical approach. Thurman believed that oppressed people hold on to kernels of truth and inspiration even when those kernels are embedded in webs of lies and mystifications—like finding a ripe apple in a bushel of rotten apples. For example, the American Dream is a falsification of history and a mystification of systemic oppression. Yet Thurman said, “Keep alive the dream; for as long as a man has a dream in his heart, he cannot lose the significance of living.” King clearly thought long and hard about this. In his rhetoric, King talked about how the American Dream was for the most part “bankrupt,” but he then went on to say that he had a different American Dream. In King’s version of the American Dream, he spelled out the aspirations of much of the black population, e.g., what the Dream could and should be. I would call King’s strategy one of ‘Critique and Affirmation’: embedding critique and truth-telling within the context of affirming peoples’ gut instinct that having a collective Dream is important.

Thurman did the same thing in a religious context. He took the classic parable of ‘turning the other cheek’ from the Sermon on the Mount, which had been used for centuries to preach passivity to slaves, and reinterpreted it (perhaps accurately). He argued that Jesus was saying oppressors keep the oppressed off balance by making them constantly react to their attacks (such as slaps). If all the oppressed do is react, they will never have the space to think for themselves, and strategize for their own liberation. So, what Jesus meant by ‘turn the other cheek’ is not to submit to oppression, but to develop enough internal fortitude to not allow slaps and blows to control your thoughts and emotions. In this way, Thurman helped transform black theology from an often passive doctrine into a militant one. I saw this in practice as a kid. The power of the approach was that it started from concepts and metaphors that people had already internalized, and then gradually changed what those concepts and metaphors meant to people.

Environmentalists and anti-war activists have a different and more existential approach; they point out that human survival on earth depends on nations cooperating worldwide to limit carbon emissions. This cannot happen if nations continue warring, or preparing to war, with one another. Peace activists also warn that many nations hold stockpiles of nuclear weapons and other nations are attempting to obtain them. We are never far from nuclear catastrophe. Survival of humanity is a second, and urgent, reason for Americans to re-examine their identities. A third existential reason is spiritual. The greatest argument for democracy and equality is the commonality of our existence: we do not know the origins of life; we do not know the reason for our existence, nor our ultimate destiny; we do not know our place in the universes; we all share life on earth only briefly. These are profound truths that animate religion and spirituality. Today’s climate deniers are not only science deniers, they deny the existential truths of human existence. They deny the fundamental tenants of religion that we love one another, and instead maintain that it is impossible to have a system of government and cooperative living that is anything more than the assertion of naked self-interest. The philosopher Hegel rightly said these latter views were the traits of a de-humanized society. Climate deniers thus, in essence, also crush the soul of our democracy. At various points of US history, other anti-humanist movements have sought to do just that. One hundred sixty one years ago, slaveowners were saying democracy doesn’t apply to black people or women. Social media at the time was mainly the church. So much of the debate centered on whether God intended for all people to be treated equal. The abolitionists said that God most loved the marginalized, the oppressed, and the meek. The slaveowners retorted that the abolitionists are spreading fake religion–the fake news of their day. When the Civil War concluded, 125,000 Union soldiers marched in jubilation through the streets of Washington, D.C.. The song they sang as they marched commemorated the great white abolitionist, John Brown, and what they called God’s truth, which was about the common humanity and equality of all people. The song was the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic:’

“John Brown’s body lies a-moldering in the grave, but his soul goes marching on. He captured Harper’s Ferry with his nineteen men so true, he frightened old Virginia till she trembled through and through. They hung him for a traitor, they themselves the traitor crew, but his soul goes marching on.

As he died to make men holy, let us live to make men free. His truth is marching on. He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat; He is sifting out the hearts of men before his judgement seat. Oh be swift my soul to answer Him! Be jubilant, my feet! Our God is Marching on. Glory, glory, hallelujah: His truth is marching on!”

In this country there is actually a great spiritual tradition of action towards multi-racial democracy (God’s “truth” of human equality), an antidote to the deep anti-democratic trends just mentioned, that must be lifted up and build upon to re-brand the meaning of freedom in America. Many in the civil rights movement took such an approach, and they learned from the experience of many wars that violence does not advance society, moral and spiritual learning does. Violence can initiate chains of revenge and resentment that block social advancement altogether. Martin L. King, Jr., noted that wars were the result of collusion between government and corporate elites, and called upon civil society to rise up (non-violently) to restore and develop democratic multi-racial governance of all of society.

Building Civic Infrastructure

Democracy, like any other institution, requires and infrastructure and resources to function. If citizens are to truly govern society, e.g., if their consent is to be well-considered and meaningful, there needs to be infrastructure and resources available to support them. Regarding resources, I mentioned three options earlier: member or community donations, corporate funding, and foundations. Government funding for civic organizations is another option, but a limited one. Government funding for civic organizing and civic media is unlikely in the short term because Americans are divided, and cannot agree on which organizations are neutral. Funding is often a form of control, and if the purpose of civil society is to make government accountable to something outside of itself (the people), having government control funding of civic organizations is a tricky problem to navigate under the best of circumstances. A serious current danger with government funding for civic organizing is that some parties will want to use such funding to build organizations that are undemocratic and potentially violent.

Another option is the most simple and obvious of all, it is to learn from those who have made progress influencing government from civil society. The standout cases have been labor unions and business advocates. Labor unions organize workers to take a bigger share of market returns (or government budgets) from employers. They then use a portion of the gains they receive to fund their own advocacy and capacity building. Businesses, far more extensively than unions, take a portion of their market profits to fund policy development and political advocacy. What we propose is innovating the labor union model beyond its origins in 19th century productivism, which focused on organizing workers in production sites, to incorporate the power of workers and their families as consumers. This is terrain productivists have largely ceded to the business community. Money gleaned from the consumer side of the market can be used to fund civic organizing, policy development, and advocacy; it is a far greater source of potential funding than what can be squeezed out of unions representing 6% of the workforce. A second benefit from this approach is that it allows communities of color control over resources they glean from community bargaining efforts. They can thus fund and scale up their own organizing and advocacy without depending on the good wishes of corporations, foundations, or other white dominated institutions.

A second, and related proposal, builds on the productivist approach of increasing democracy at workplaces, by broadening the notion of “private businesses” to “civic businesses.” To clarify the difference, it again helps to go back to the early period of business development in the US. The first large businesses in the US were slave plantations. It was slaveowners who insisted that their business operations be considered entirely private, immune from the democracy being established as the country’s ethos. This was a hypocritical stance from the beginning, as noted at the time, since plantations were never “private,” they depended on government (the public) to repress slave rebellions, catch runaways, and provide other services. Plantations were autocratic in the extreme; slaves were often whipped to increase productivity, which became a norm for increasing economic “efficiency.” These plantation ways of thinking about business organization–top down, oppressive, workers having no voice—became a norm for business management in general. The idea that businesses could help train workers in participatory governance, or that businesses could be venues for peoples’ control of economic decision making, or that equality could be a boon to economic performance rather than an impediment to it, sounds strange in the US because we have not yet fully reconstructed the economy from our slavery background. Yet, there is no inherent reason why businesses cannot be turned into organs for strengthening civil society the same way that labor unions can. Creating such “mission oriented” businesses that can allocate a portion of their earnings for advocacy and civic capacity building is another pathway for funding civil society. One can imagine that with a proliferation of civic businesses and consumer bargaining units (community collectives) rooted in different communities, there will be opportunities for mergers and acquisitions among them that will involve not only money but earnest and free discussions about our racially divided past and shared dreams for the future. This would be progress towards multi-racial ED.

Alienation

Descriptions, complaints, and academic arguments about alienation tend to come in two forms: the desire for freedom against government domination and bureaucracy, and a more recent similar fight against corporate domination and bureaucracy. Western accounts of freedom in the context of community describe the emergence of a “public sphere,” meaning civil society and as an autonomous part of society free from domination by the state. In recent decades, there’s also been a third line of critique directed against embedded racism and patriarchy within civil society itself. The racial critique is that there’s been a silence in much of the civil society literature and discourse about systematic oppression of non-whites, including slavery, segregation, and the outright exclusion of people of color (especially blacks) from so-called free civic and market institutions. The race issue is typically considered as a “problem” associated with people of color, but race is a steering construct for white Americans as much as it is for any other group. White’s predominant conception of freedom as negative and procedural, and the continued celebration of Western society’s racialized civic culture, in a DuBoisian line of critique, leads whites to misdirect alienation in their own lives towards people of color. That is, most Americans, including whites, work under conditions of neo-dictatorship in their workplaces, having no voice in firm goal-setting or operations; they are declared free, but many do not feel that way. Ordinary Americans pay substantial sums in taxes (while Amazon paid no income taxes last year) for military, police, and prisons to enforce racial domination and corporate interests (such as oil), yet feel their urgent needs and hopes aren’t met. Moreover, because of inequalities and resentments built up over centuries, Americans live in fear of each other, especially whites’ fear of non-whites. Citizens are armed to the teeth, mass shootings and suicides are frequent, and drug abuse is rampant. If this is what freedom represents, many people lose hope in a better America, and in democracy. Alienation is widespread, and as the world watches, the lure of American democracy is diminishing. Yet, few whites connect these ills (and their own alienation) to America’s origins in slavery and racial segregation, and to their own concept of themselves as “white,” even if they’ve never met a black person.

Going back to Abraham Lincoln, his greatest worry on the heels of the Civil War was that most white citizens did not want to be part of the same community and polity, and certainly not put on an equal footing with black people. This is still the main alienation in US society. Economic inequality and government unaccountability, in the eyes of many whites, are the result of unfair advantages handed out to people of color. The pathway to changing the economy and government is to unite Americans, but unity necessitates overcoming this white racial resentment, which is so strong that it threatens the foundations of democracy. One need only look at the Republican Party’s opposition to the right of all Americans to vote, because they believe universal voting access undermines their ability to win elections as an all-white minority party. People of color’s demand for equal treatment threatens what many whites believe has made America a successful country, and it also threatens their superior sense of personal self-worth and backing from government. How to generate a will for unity in the midst of such distrust and dislike is the content of the racial alienation problem.

The starting point for building unity across race, in my view, is changing white American’s image of black people as wanting to take material things away from white people. Black, and other people of color, need to advocate a broadly appealing economic platform to dispute that image. A forward-looking economic platform could meet white workers where they are, and help move them away from a zero-sum calculation that they have nothing material to gain by uniting with people of color. But this is only a first step; an economic platform will not fully remove the anxiety many whites feel about no longer being a demographic majority, with the ability to dominate society. As we noted earlier, another step must be engaging whites and people of color in moral discourse, as Martin Luther King tried to do with his image of a ‘beloved community.’ What would it be like to live in a world not consumed in hate and defensiveness, full of police and nuclear weapons? Why do we still adhere to notions of inferior and superior human beings? How does our culture continue to nurture these images? ED cannot settle for being an economic platform only, if ED does not address these moral questions that divide the nation, it will flounder on the same rocks—of short-sighted calculations of group self-interest–that have long undermined broader support for labor unions.

Advocating for system change, whether in creating a new economy, or in changing how we conceptualize labor and community organizing, or overcoming alienation in civil society, requires imagination. Even harder is awakening imagination amongst those who don’t know they lack it: “the absence of imagination has itself to be imagined.” Another area, besides race, where this is particularly true is in the relation between women and the economy. The US model of corporations as private entities, with no particular obligations to serve the public, stems from a long and largely unquestioned tradition of treating the work of nurturing, educating, and caring for children, families, the sick and elderly as unpaid ‘women’s work.’ Price theory has nothing to say on this issue. Productivists have also downplayed women’s issues historically, since most women were not working in factories or other ‘points of production.’ There is little doubt, however, that democratic engagement of women in economic decision-making would prioritize the issue of unpaid, or demeaned and underpaid, women’s work in reproducing and caring for human beings. The exceptional income disparities in the US are a direct consequence of women’s oppression (the thinness of ‘negative freedom’), for it is women who are most affected by the absence of quality publicly funded universal childcare, the absence of guarantees for affordable housing, the absence of sufficient funding for quality K-16 education, the absence of adequate and healthy food for millions, and the absence of quality universal healthcare. These absences only ‘make sense’ because women (and today, often immigrant women) are expected to work in these areas for very low pay, effectively working as semi-slaves.

Technology

In envisioning a future economy it is important to ground utopian goals in existing economic capabilities, e.g., “the forces of production.” Those capabilities are being driven by dynamic advances in science and technology in areas such as robotics, artificial intelligence, and gene-editing. These advances are poised to transform manufacturing, transportation, human services, energy, housing, education, communications, and healthcare—for better or for worse. Companies driven narrowly by profit-seeking have an incentive to deploy technology to replace human labor—causing unemployment. Ironically, these new technologies lower the cost of manufacturing and service provision dramatically, making it feasible to satisfy basic human needs worldwide. The conundrum is that even with technology providing the capability for abundance, technology’s ownership structure is undermining economic expansion because profit-seeking firms do not want to share the financial benefits of science and technology with workers and communities. And, unemployed and underpaid workers cannot buy many goods on the market. As mentioned earlier, Silicon Valley firms are promoting universal basic income (UBI) as a solution to this weakening of consumer demand, and as a way of calming resistance to big tech’s impact on vulnerable workers. UBI, however, is at best inadequate and short-sighted. As long as the design and use of technology is governed by short-term profit-making, it will further displace workers whose purchasing power is needed to sustain markets. The continued application of new technology will thus increasingly slow the economy down, and require ever more government intervention (more and more UBI) even to maintain workers at poverty levels. This leads to a downward spiral of economic stagnation—one we are already on, that makes little sense other than protecting extraordinary profits for small numbers of owners and investors.

Used differently, technology could help create a very different future. Even a brief exploration can show this. Take battery powered vehicles. Most auto companies plan to convert to 100% battery powered vehicles in the near future. Battery powered vehicles consist simply of a battery and assembled parts, they can be manufactured and assembled in cities. Moreover, with computer-driven machinery, they can be designed with customer input and produced on the spot. The “autoworkers” will be designers and operators of advanced machinery. The “car” in an urban setting may be closer in size to a shopping cart than today’s conventional cars. Moreover, future cars will be “smart,” meaning often driverless, with traffic being regulated by AI via the Internet. Smart cars offer the option of ride-sharing on an extensive level; customers can use their smart-phones to call circulating driverless rideshare vehicles to take them where they want to go. Some transportation futurists predict such ridesharing will lead to far fewer individually owned vehicles, perhaps urban reductions by as much as 90 percent. The shift to smaller battery powered vehicles and fewer cars will lesson the need for entire streets and parking lots devoted to cars. This would open up space in cities that can be used for integrated affordable housing, planting trees, and beautifying cities (public art).

Concurrent with new thinking about transportation is ocean sea-level rise and the need for carbon reduction. Two-thirds of the human population live in cities vulnerable to sea-level rise. New York City alone has 520 miles of ocean shoreline. As the ocean rises, cities will have to not only mitigate water rise through things like levees, but adapt to the ocean reclaiming land in many places. Ocean level rise is certain to force enormous rebuilding and relocating. This will create a huge number of jobs, and with sufficient job training and decent wage standards, it could create a pathway out of poverty for millions. Rebuilding also creates opportunities for creating energy in new ways, such as turbines that could possibly harness the energy of ocean tides as they pass through cities. Yet, crucially, this upheaval, in combination with changes in transportation noted above, creates an opportunity for citizens to remake cities to be inclusive, broadly prosperous, and beautiful, as well as green. Realizing opportunities for a better future requires that citizens be aware such opportunities exist, and are within their power to bring about. ED is shorthand for building the civic infrastructure to bring about such citizen awareness and capacity. With technology constrained by the narrow aims of corporate profit-making, its potent potential to enable human progress is veiled.

IV. Conservative Counter Arguments

The Private Sector Should Be Left Alone

Conservatives often argue that the private sector, if left alone by government and labor unions, will create prosperity for all through “the invisible hand.” Both the productivists and price theorists have long imagined that there is such a thing as an internally driven “private sector” that flows independently of government. This view is fatally misleading. Government makes the rules that create markets—in the same way that one cannot play a game of chess without rules to govern the movement of pieces. A key feature of a market economy, for example, is free and fair competition between firms. Without government oversight, larger companies typically buy out or undermine smaller firms, so that they can charge monopoly prices to consumers (this is the opposite of market efficiency). Many firms also, in their relentless pursuit of profits, pay as few taxes possible, avoid environmental regulation, and drive down wages. This leads to weakened national infrastructure and workforce capabilities, and erodes the social and ecological resources that all firms depend upon. Without government adeptly regulating business, firms focused narrowly on their own self-interest undermine social stability and imperil the earth. Far from being a hindrance to markets, strong government is critical for markets to function sustainably without causing social and environment distress.

The above is not an argument for abolishing markets altogether. Markets allow people, firms, and localities, to specialize in what they do best while trading for things others do better. Markets are the best means societies have found for meeting wide-ranging consumer demand for specialized goods and services. In regulating or designing markets, however, their downsides must also be kept in mind. We can see how allowing a sub-set of market actors (big corporations) gain too much power, as happened in the US in recent decades, undermines social well-being. Corporate executive pay and payouts for shareholders has surged in large part due to their ability to press government for tax leniency. A consequence is less federal revenue, leaving the nation’s infrastructure in taters and workers’ social mobility among the worst in the industrialized world. Funding is so low for education that the US can’t meet the need for highly trained scientists and engineers; they must increasingly be recruited from other countries.

Racial division, we have also noted, was cultivated within civil society to keep workers weak and divided. When private market actors have too much power, they use it to deepen social divides beyond race. Conservatives, for example, are pushing for the privatization of social security. Their goal goes beyond helping fund managers earn more commissions, there’s a political angle as well. Privatizing social security would encourage many seniors to push for higher dividends to their pension funds, and to oppose decent pay for workers. It’s a way of winning political allies for Wall Street by pitting grandparents against their grandchildren. Similarly, when affordable housing was financed through corporate tax write-offs (tax credits), community developers were encouraged to cheer for Wall Street profits over the demands of workers for higher pay–another way to divide communities. Yet, research has definitively shown (see Elinor Ostrom) that such divisions and the pursuit of individual self-interest do not produce superior economic outcomes as compared to cooperation within firms and across society.

Markets are poorly suited for some initiatives, for example, projects that are hugely expensive to develop, take a long time, are highly risky, or serve society in common. Long-term infrastructure, like high speed ‘bullet trains,’ for example, are too expensive and difficult to build to allow for competing “bullet” rail lines (market competition). Such infrastructure is best financed and overseen by government. Government is also better at solving ‘first mover’ or ‘collective action’ problems. For example, imagine two companies, one makes electric cars and the other makes car-charging stations for electric vehicles. Car manufacturers hesitate to build battery cars until there is an extensive array of charging stations that can keep the cars running. But, the charging station manufacturers put off building an array of charging stations unless there are enough electric cars to make it worth their investment. So, nothing happens. In situations like this, government can invest in the charging stations while luring in the electric car manufacturer. Government adds economic value, as Keynes said, by doing things the market won’t.

Economic Democracy Undermines Freedom in Favor of Totalitarianism

Another popular conservative argument is that interference with the “free market” based on consumer choice inhibits individuals’ freedom. Engaging citizens to set collective economic goals at any level raises the prospect of economic planning to help implement these goals. Conservatives frame economic planning as social coercion. The influential Austrian conservative economist Friedrich Hayek argued that markets do a better job incorporating individual innovation than planners can. Yet, Hayek ignored an important reality; big corporations already do immense planning for example, to understand market trends, influence consumers, steer government legislation, and often to dominate markets — not usually to unleash the innovations of small entrepreneurs. Hayek’s anti-government, anti-planning bias also meshed well with American business’s traditional opposition to government regulation—which, again, goes back to slavery.

Still, Hayek’s challenge to ED raises a substantial issue. Would citizen oversight of major economic decisions necessarily lead to centralizing information and power in the hands of elite experts? What level of citizen oversight is realistic? Hayek believed that ordinary citizens cannot handle much information or do a lot of independent thinking. He thought that community organizing quickly turns into irrational mob action (as he saw in Europe during the rise of fascism), which is probably why he put more faith in markets as a more democratic mechanism than citizens coming together to reason and plan. Hayek hoped that citizens would be comforted enough by capitalism’s material comforts to reject grassroots action in politics.

There is little question that uninformed and untrained citizens cannot be expected to make wise decisions concerning complex policy matters (that’s why civic infrastructure is so important). The related question is how much information can sensibly be conveyed to citizens, and how much training is possible? As in any major endeavor, the answer depends on both social ingenuity and technology. There are examples of extensive worker training and effective decision-making in worker-owned firms in Spain and elsewhere. But, we need a lot more experimentation and practical learning to develop this field. Technically, it’s never been easier to convey information to ordinary people. Inexpensive technology exists today, like smart phones, that can make information that was once difficult to obtain widely accessible. Technology can enable ordinary people to coordinate and collaborate around their higher values and principles–not just on negotiating prices and immediate self-interests. Social ingenuity exists too. For example, a group of progressive bankers in England (such things exist over there) developed a mobile phone APP that allows consumers to scan items in the supermarket. The APP shows what the producer of the shelf item pays their workers, the producers’ carbon footprint, and where they get their financing. Consumers can choose to support the green producer or not, or choose to support pro-labor employers if they so desire. This example shows how civic organizing and solidarity can be extended using a market mechanism. In fact, having only price and ingredient information available on consumer items, when people care about so many other issues, is itself a form of social coercion through the market, not the freedom that Hayek claims. Building the APP took ingenuity: a lot of meetings and planning sessions between groups that don’t regularly collaborate including labor and green activists, along with the bank. Rather than trying to pass government regulations banning bad employers and dirty companies, and building on their years of organizing work, they took a quicker route of simply allowing people to choose green and labor-friendly products through the market.

Citizen control of the economy raises nearly identical issues as citizen control of government. If people are skeptical about citizen’s ability to govern the economy, it’s because citizens aren’t carefully overseeing government either—even though this is supposed to be the foundation of a government based on citizens’ consent. Citizen governance, whether of government or the economy, requires civic infrastructure to engage, inform, and train citizens. There are some instances in US history where such infrastructure was developed with government support, such as during Reconstruction, and the roll-out of the Tennessee Valley Authority and rural agricultural cooperatives under President Roosevelt. The Roosevelt Administration also proposed the Industrial Recovery Act to rebuild manufacturing on a more democratic basis (regulating big businesses, increasing the role of labor and small businesses) during the Depression, but the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional.

Hayek was dead wrong about community participation invariably leading to demagogy and anti-democratic movements. The civil rights movement used community participation to deepen democracy, as did the Black Lives Matter movement. Most people are educatable. In NYC, for example, we learned that if we inform ordinary people about the basics of infectious disease, and make resources available to responsible local community-based organizations, the vast majority of people will adjust their behavior for the good of society. If we had not worked through trusted intermediary community organizations, and left control of Covid to the medical vaccine specialists, many more people would have died before vaccines arrived. Civic participation, when informed and deliberate, is a good thing for society.

Hayek conceded that human beings are by nature social beings, but the operative emotion for his theory remained individualism and self-interest. This is the instinct that free-market capitalism celebrates, yet it is rebuked by modern psychology and behavioral science, not to mention practical experience. Hayek also operated at such a level of abstraction it allowed him to avoid real-life contradictions to his theory. The free market hasn’t, as Hayek predicted, been a universally democratizing force. It didn’t undermine slavery and hasn’t made white Americans anti-racists. Capitalism is currently thriving in very undemocratic countries.

We urgently need community (civic) engagement, planning, and design to help avoid environmental catastrophe, improve public health, to engage and support disconnected youth, and ensure economic security for all—all the things markets are not doing. Hayek’s challenge is whether such planning compels us to operate our societies more undemocratically, by being governed by technocratic elites. In other words, Hayek asserts that civic engagement will ultimately make people more powerless. ED has more confidence in citizen’s capacity for responsible governance of the economy.

Economic Democracy is Socialism in Disguise

Does ED mean replacing capitalism with socialism? The short answer is, “no, not necessarily.” A better answer is that the question is irrelevant. To understand why, we need to notice two things about capitalism. Every capitalist country has already, because of popular pressure, incorporated aspects of socialism. Social security, universal healthcare, and life insurance were all socialist ideas. Every socialist country, also under pressure, has incorporated aspects of capitalism. China, a socialist country, is one of the largest capitalist systems in earth. The terms ‘capitalism’ and ‘socialism’ do not capture the complexity, dynamism and syncretic of modern economies. Moreover, capitalism is not a free-floating economic system that looks the same regardless of government policies and social structures. Capitalism in China is very different from capitalism in Japan. Capitalism in Sweden and Finland are very different systems from capitalism in the United States. Modern economies may be better conceptualized as culturally and institutionally influenced inter-weavings of three types of economic structures: private ownership, civic (and non-profit) ownership, and government ownership.

Another approach to answer the ‘capitalism vs. socialism’ question is to break the economy down into sectors. Different sectors of the economy are already more ‘capitalist,’ more ‘socialist,’ or more ‘civic.’ For example, government planning and ownership seems to be the only way high-speed rail has developed anywhere in the world. China’s government is now developing 13 high-speed railways; the US, largely because of the anti-government influence of price theory, hasn’t developed a single one. On the other hand, China is far behind the US in developing computer Apps. Most Apps come from small firms (including coops) having few limits on experimentation by highly-trained employees, and a culture of open discussion and dense sharing of ideas—often over the Internet. This is pushing China to open more opportunities for citizen exchanges, which seems to work best for APPs, so that they can compete with the US. If the US develops high speed rail, it will probably be a government project similar to China’s. In other words, the mega ‘capitalism versus socialism’ distinction is not very helpful in thinking about how economies operate. A better approach is to ask, ‘which institution or economic lever is best suited for X’; or ‘which combination of economic levers are best for X.’

V. Criticisms from the Left

Markets Are Bad

Often people on the Left oppose anything supporting ‘business’ or ‘markets’ as capitalistic, and inherently bad for workers and communities. Yet, markets existed before capitalism, and Marx argued there would be a role for markets after capitalism. Markets are a kind of game (with real stakes) designed to induce competition for the purpose of increasing efficiency in making something, or increasing diversity among products. Markets have winners and losers, just like games. Markets also don’t determine what kind of culture or institutions design them. Markets did not require slavery and colonialism, and there is nothing that requires markets to give winners huge rewards and losers little or nothing. I suspect that people who object to using markets to promote social justice are not so much opposed to competition or diversity in products as they are opposed to the US structure and culture of capitalism, which shapes how we experience markets in daily life.